Comparaison des causes de décès maternels dans deux hôpitaux tertiaires de pays subsahariens

On estime que 585 000 décès maternels surviennent chaque année dans le monde, dont 90 % dans les pays en développement, en particulier en Afrique subsaharienne et en Asie[1]. L'amélioration des soins maternels est donc une priorité mondiale majeure. Pour y parvenir, plusieurs interventions et initiatives ont été mises en œuvre dans les pays, telles que la mise à disposition d'accoucheuses qualifiées, des sessions de renforcement des capacités, l'augmentation de la couverture des services prénatals et la promotion de l'accouchement avec des accoucheuses qualifiées. Ces interventions se sont rapidement multipliées entre 1990 et 2015 grâce aux efforts renouvelés des Nations unies pour réduire de 75 % la mortalité maternelle d'ici à 2015, ce qui constitue l'objectif n° 5 des objectifs du Millénaire pour le développement (OMD). Bien qu'une baisse de 29 % des décès maternels ait été observée après cette période, 289 000 femmes meurent encore chaque année de complications maternelles[2]. Les données disponibles montrent que la majorité de ces décès maternels surviennent dans un établissement de santé, ce qui soulève la question de la qualité des services maternels fournis[3]. Pour répondre à cette question, il est essentiel de bien comprendre les causes des décès maternels, les facteurs associés et de mettre l'accent sur les retards de type 3. Cet article examine les causes des décès maternels dans deux hôpitaux tertiaires de deux pays d'Afrique subsaharienne (le Nigeria et le Liberia), ainsi que leur comparaison.

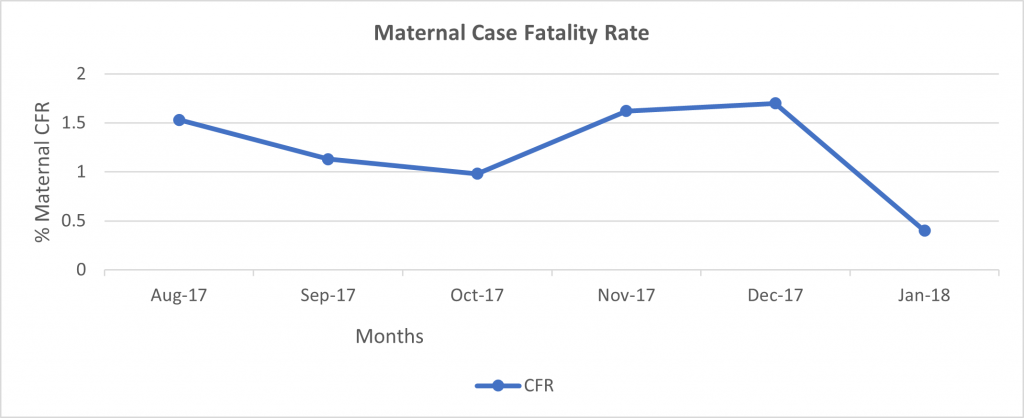

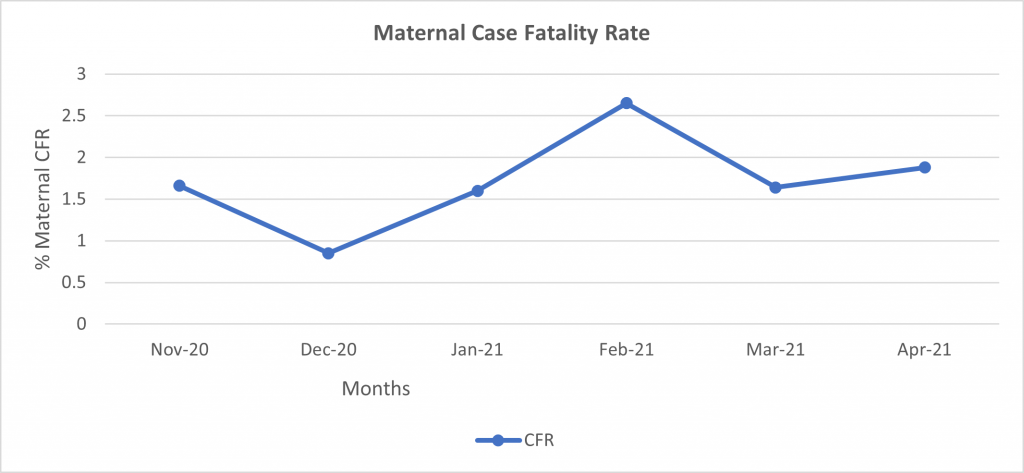

Un examen rétrospectif sur six mois des dossiers médicaux de tous les décès maternels dans les deux hôpitaux tertiaires d'août 2017 à janvier 2018 (pour le Nigéria) et de novembre 2020 à avril 2021 (pour le Libéria) a été réalisé. Dans l'hôpital nigérian, un total de 1 685 accouchements ont eu lieu et 21 décès maternels ont été enregistrés au cours de la période examinée. Cela donne un taux de létalité moyen de 1,25 %(voir figure 1 ci-dessous). Les trois principales causes directes de décès maternels étaient l'éclampsie (57%), l'hémorragie (10%) et la septicémie (10%). En outre, la plupart (90 %) de ces décès maternels concernaient des patientes qui n'avaient pas été inscrites, ce qui permet de conclure à l'existence d'une relation entre les soins prénatals et l'issue de la grossesse. Dans l'hôpital libérien, au cours de la période examinée, 2 171 accouchements et 40 décès maternels ont été enregistrés. Le taux moyen de létalité maternelle était donc de 1,84 % (voir figure 2 ci-dessous). Les principales causes directes de décès maternels étaient l'hémorragie (30 %), l'éclampsie (20 %) et la septicémie (18 %). Cependant, en raison d'une documentation insuffisante, aucun détail supplémentaire n'a été obtenu, mais les cliniciens interrogés ont confirmé que la plupart des décès maternels étaient des cas non répertoriés.

Dans les deux hôpitaux, les causes indirectes des décès maternels étaient un mauvais comportement de recherche de santé, des barrières financières, des croyances culturelles, une présentation tardive et des barrières institutionnelles. Les barrières institutionnelles, qualifiées de retard de type 3, comprennent le manque d'équipement de base et la rupture de stock de médicaments vitaux, le nombre insuffisant d'accoucheuses qualifiées, le manque d'application et de respect des protocoles/directives, et le manque d'importance accordée aux services centrés sur le patient.

Par conséquent, une approche holistique qui donne la priorité aux intrants et à la mise en œuvre d'une initiative de qualité visant à éliminer ces obstacles entraînera une baisse de la mortalité maternelle. Une approche qui implique une réflexion systémique, l'engagement des parties prenantes, le renforcement des capacités, l'application du modèle d'amélioration, la gestion des performances et l'acquisition des intrants nécessaires permettra de réduire le nombre de décès maternels dans les établissements de santé. L'utilisation de l'approche holistique décrite ci-dessus sur une période de 30 mois (février 2018 - juillet 2020) dans l'hôpital tertiaire nigérian a entraîné une baisse des décès maternels en établissement. Sur la base des enseignements tirés de l'hôpital nigérian, l'approche est mise à l'échelle dans l'hôpital libérien, qui présente un contexte similaire sur une période plus courte (12 mois).

Source :

[1] Réduction de la mortalité maternelle. Déclaration conjointe OMS/FNUAP/UNICEF/Banque mondiale. Genève 1999

[2] Kassebaum NJ, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990-2015 : a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015 (Niveaux mondial, régional et national de mortalité maternelle, 1990-2015 : une analyse systématique pour l'étude sur la charge mondiale de morbidité 2015). Lancet 2016 ; 388:1775-812.

[3] Collaboration pour le compte à rebours 2030. Countdown to 2030 : tracking progress towards universal coverage for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (Compte à rebours vers 2030 : suivi des progrès vers la couverture universelle en matière de santé reproductive, maternelle, néonatale et infantile). Lancet 2018 ; 391:1538-48.

Spécialiste des subventions et du développement des entreprises

Nous sommes à la recherche d'un spécialiste des subventions et du développement commercial très motivé et expérimenté pour rejoindre notre organisation. Le candidat retenu sera chargé d'identifier les possibilités de financement, d'élaborer des propositions de subventions et de favoriser les partenariats avec les donateurs potentiels et les parties prenantes (régionales et mondiales). Cette fonction joue un rôle essentiel dans l'obtention de fonds et de ressources pour soutenir la mission et les projets de notre organisation.

Postulez maintenantConsultant en santé publique, Guinée

Le consultant (en collaboration avec l'équipe de l'accélérateur) recueillera les résultats de l'outil, organisera une réunion avec les parties prenantes pour discuter des résultats de l'outil et produira un rapport sur les principales conclusions et recommandations de l'outil qui sera diffusé publiquement.

Postulez maintenantAttaché de santé publique, Sénégal

Nous sommes actuellement à la recherche d'un professionnel expérimenté de la santé publique au Sénégal pour travailler sur la plateforme anticipée de développement des capacités et de financement de la nutrition et fournir une assistance technique pour élever le financement de la nutrition et renforcer les capacités locales pour soutenir ces efforts. L'associé doit être bilingue (anglais et français).

Postulez maintenant