Assessing preferred referral destinations of individuals identified with hyperglycaemia and elevated blood pressure on the Diabetes Awareness and Care (DAC) project in Imo state.

Authors: Geoffrey Anyaegbu | Chinonyerem Egekwu | Christine Ezenwafor | Christiana Osuji

Executive Summary/Key points

- Diabetes and hypertension are chronic diseases with high morbidity and mortality worldwide.

- On the DAC project, we followed up with 71 individuals identified with hyperglycaemia and elevated blood sugar levels who were referred to secondary hospitals for expert management. Follow up period was between September and October 2021.

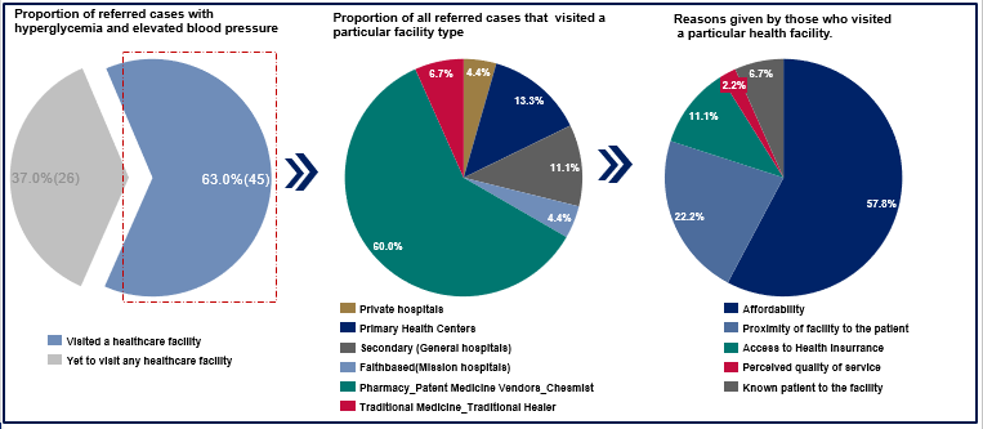

- 60% of these individuals visited pharmacy stores or patent medicine vendors while others visited secondary health services (private hospitals – 4.4%, general hospitals – 11.1%, faith-based hospitals – 4.4%) for expert management.

- Referred patients cited affordability as the primary reason for not visiting a healthcare facility

- Improving diabetes and hypertension management in Imo State will require institutionalizing policies that mitigate huge out-of-pocket expenditures, large health promotion activities and effective regulation of healthcare providers.

Background

Diabetes and hypertension are chronic diseases whose prevalence have been on the increase in a decade and are a major cause of premature death [1,2]. In its latest report, International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimates that 537 million adults (20 – 79 years) are now living with diabetes worldwide. [3]. This estimate is likely to rise to 783 million by 2045 [4]. Globally, about half (44.7%) of the people living with the disease are undiagnosed [3]. Furthermore, it is estimated that 541 million adults globally have Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT) which increases the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [5]. T2DM accounts for 90% of the cases of diabetes around the world.[2].

Currently, there are 24 million adults estimated to be living with diabetes in Africa [4]. Nigeria contributes the second highest number of persons living with diabetes with 3.6 million people on the continent [4]. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), more than half (53%) of the people living with diabetes in Nigeria are undiagnosed [6]. Similarly, about 1.28 billion adults aged 30-79 years are living with hypertension and a majority (two-thirds) live in low- and middle- income countries [1]. Similarly, the prevalence of hypertension in Nigeria is 38.1% with an estimated 76.2 million adults living with hypertension [7]. If this trend continues, the incidence of stroke, heart failure, and kidney damage may be on the rise.

The Nigerian healthcare system is weak and ill-equipped [8] to handle complications resulting from hypertension and diabetes. Inadequate human resources for health and poor healthcare financing have posed a serious challenge to the healthcare system. For example, evidence shows that diabetes specialists in Nigeria are significantly in short supply [9]. The estimated ratio of diabetes specialists to the population is as low as 1 to 600,000 and many of them work in tertiary healthcare facilities which are in the cities [9]. Thus, patients in rural communities who need specialized diabetic care may experience delays in receiving appropriate care. Furthermore, the cost of treating diabetes and hypertension in Nigeria is on the increase. Currently, it is estimated that the average cost of managing diabetes is between ₦300,000 and ₦500, 000 per patient [10]. This cost can increase to N2,000, 000 when complications such as diabetic foot ulcers and kidney failure occur [10]. In the same vein, it is estimated that the average annual total cost of managing hypertension is ₦145, 086 per patient [11]. Regrettably, most of these costs are incurred by the patients due to the high out-of-pocket expenditure (70.5%) [12] and poor (<5%) coverage of social health insurance in Nigeria [13]. This could result in catastrophic health expenditure considering the grossly inadequate minimum wage of ₦30,000 [14] and the increasing inflation rate in the country. However, early diagnosis and appropriate referral system are effective in mitigating complications and mortality due to diabetes and hypertension. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that when referral systems are effectively integrated into primary care, morbidity, and premature mortality from major non-communicable diseases such as hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus are significantly reduced. [15]

Between June 2018 and October 2021, the Diabetes Awareness and Care (DAC) project was implemented in Imo State. This was a collaboration between the Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) unit of the Federal Ministry of Health and the Health Strategy Delivery Foundation (HSDF) and led by the Ministry of Health in Imo state. One of the three objectives of the DAC project was to improve access to diabetes care through the training, screening, and referral of individuals with hyperglycemia and elevated blood pressure to secondary healthcare facilities for expert management.

In this policy brief, we share insights about the referral destinations of individuals referred for hyperglycaemia and elevated blood pressures in 12 DAC project intervention communities in Imo State over a two-month (September and October 2021) period. Also, we will discuss recommendations for policymakers to improve the management of diabetes and hypertension in Imo State.

Approach

In the months of September and October 2021, we tracked (via phone calls) 71 newly identified individuals with hyperglycaemia and elevated blood pressure who were referred to secondary healthcare facilities for expert management. Two weeks after these individuals were identified at community outreaches in Imo, we called them and used a structured questionnaire to inquire if the individual had visited a secondary health facility, what type of healthcare facility was visited, and the reason for the facility selection.

Results

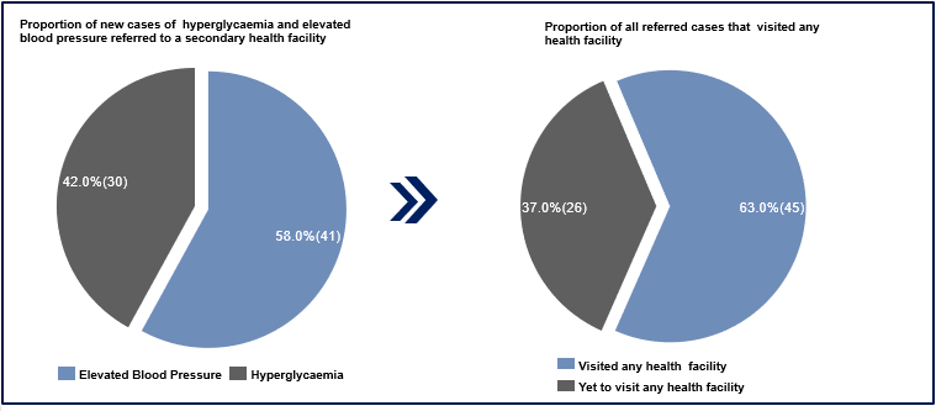

Of the 71 individuals tracked, 58% (41) had hyperglycaemia while 42% (30) had elevated blood pressure (Figure 1). Also, of the 71 referred, 63% (45) visited a health facility, while 37% (26) had not visited a health facility at the time of the call (Figure 1).

Of the 45 persons that visited the facilities, the majority 60% (27) visited pharmacies and Patent Medicine Vendors (PMV) to access care (see figure 2). While 20% (9) visited secondary healthcare facilities which included private hospitals (4.4%), general hospitals (11.1%), and faith-based hospitals (4.4%) (Figure 2). Respondents that visited pharmacies and PMV reported high cost of services (affordability) as a primary reason for not visiting a health care facility (57.8%) (Figure 2).

Currently, Imo state has an out-of-pocket health expenditure of 90.5% which is high when compared with WHO recommendations of 30-40% [16]. One of the reasons for this is because the current health insurance coverage in the state remains below 1% of the population [16]. Evidence from Nigeria has shown that most patients prefer pharmacy-based hypertension care over hospital-based care due to affordability, and easy accessibility of pharmacy shops [17]. Hospitals are associated with long wait times, high cost of care, and access-to-care challenges [17].

Recommendations

- Effective health education and promotion activities

The Imo State Ministry of Health should engage in consistent massive health education and promotion activities to educate the public on proper NCD prevention, care, and management. This can be achieved using the traditional media such as radio and television stations. Evidence across developed and low-middle-income countries supports the effectiveness of mass media campaigns in addressing NCDs and other public health challenges. Studies from Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Australia show that mass media was effective in the prevention of NCDs [18] oral cancer [19], and smoking [20]. Again, a study conducted in 10 low- and middle-income countries concluded that television adverts that graphically showcase the harms of tobacco use are likely to be effective with smokers [21].

- Improve health insurance coverage

There should be an accelerated sensitization of the citizens on the benefits of health insurance while the Imo State Ministry of Health should expedite efforts towards the full operationalization of the State Health Insurance Scheme. There is an established association between health insurance and treatment possibilities for NCDs. El-Sayed and colleagues in their study found that insurance was associated with increased treatment likelihood for NCDs in LMICs [22]. Thus, they concluded that health insurance will be a veritable policy tool in reducing inequities in NCD treatment by household wealth, urbanicity, and sex in LMICs [22].

- Effective regulatory policies

The Imo State Ministry of Health should ensure adequate regulation of PMVs, pharmacy stores, and traditional healers to ensure that they operate within stipulated and approved guidelines. A study in Zambia demonstrated that the implementation of guidelines by medicine regulatory agencies was associated with increased referral to public facilities, indicating their potential to contribute to stronger health systems in rural Zambia [23]

Conclusion

Our intervention showed that most people referred to secondary healthcare facilities on account of hyperglycaemia and elevated blood pressure preferred to access care at pharmacy stores and PMVs. The main reason for this is the high cost of care at secondary healthcare facilities. Extensive health insurance coverage could reduce high out-of-pocket health expenditure in Imo State and improve access to appropriate therapeutic care for diabetes and hypertension.

References

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension

- https://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes#tab=tab_1

- https://www.idf.org/news/240:diabetes-now-affects-one-in-10-adults-worldwide.html

- https://diabetesatlas.org/data/en/indicators/1/

- https://diabetesatlas.org/

- https://diabetesatlas.org/data/en/country/145/ng.html

- https://guardian.ng/features/76-2m-nigerians-are-hypertensive-but-only-23-million-on-treatment/)

- Welcome M,O. (2011) ‘The Nigerian Health Care System: Need for Integrating Adequate Medical Intelligence and Surveillance Systems’, J Pharm Bioallied Sci 3(4):470-8. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.90100.

- Ugwu, E., Young, E. and Nkpozi, M. (2020) ‘Diabetes Care Knowledge and Practice Among Primary Care Physicians in Southeast Nigeria: A Cross-sectional Study’, BMC Fam Pract 21, 128 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-020-01202-0

- https://www.vanguardngr.com/2021/11/diabetes-treatment-costs-soar-as-nigerias-silent-epidemic-rages/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CCurrently%2C%20the%20cost%20of%20treating,5%20million%20to%20N2).

- Abubakar, I. Obansa, S. (2020). ‘An Estimate of Average Cost of Hypertension and its Catastrophic Effect on the People Living with Hypertension: Patients’ Perception from two Hospitals in Abuja, Nigeria’ International Journal of Social Sciences and Economic Review, 2(2), 10-19 https://doi.org/10.36923/ijsser.v2i2.62

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS?locations=NG

- Oguejiofor, O, Odenigbo, C., Onwukwe, C. (2014) ‘Diabetes in Nigeria: Impact, Challenges, Future Directions’ Endocrinol Metab Synd 3: 130. doi:10.4172/2161-1017.1000130)

- https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/507087-nigerias-minimum-wage-grossly-inadequate-cant-meet-basic-nutritional-needs-of-an-adult-report.html

- WHO (2020) Package of essential noncommunicable (PEN) disease interventions for primary health care in low-resource settings. https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/essential_ncd_interventions_lr_settings.pdf

- Imo State Ministry of Health (2019). Estimating Household Healthcare Expenditures for Imo State

- Cremers, A. L., Alege, A., Nelissen, H. E., Okwor, T. J., Osibogun, A., Gerrets, R., & Van’t Hoog, A. H. (2019). Patients’ and healthcare providers’ perceptions and practices regarding hypertension, pharmacy-based care, and mHealth in Lagos, Nigeria: a mixed methods study. Journal of hypertension, 37(2), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000001877

- Tabassum, R., Froeschl, G., Cruz, J.P., Colet, P.C., Dey, S. and Islam, S.M.S. (2018) ‘Untapped Aspects of Mass Media Campaigns for Changing Health Behaviour Towards Non-Communicable Diseases in Bangladesh’ Global Health. 14(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0325-1

- Saleh, A., Yang, Y.H., Wan Abd Ghani, W.M., Abdullah, N., Doss, J.G., Navonil, R., Abdul Rahman, Z.A., Ismail, S.M., Talib, N.A., Zain, R.B. and Cheong, S.C. (2012) ‘Promoting Oral Cancer Awareness and Early Detection using a Mass Media Approach’ Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.13(4):1217-24. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.4.1217

- White, V., Tan, N., Wakefield, M. and Hill, D. (2003) ‘Do Adult Focused Anti-Smoking Campaigns have an Impact on Adolescents? The Case of the Australian National Tobacco Campaign. Tob Control. Suppl 2(Suppl 2):ii23-9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12878770/

- Wakefield, M., Bayly, M., Durkin, S., Cotter, T., Mullin, S. and Warne, C. (2011) ‘Smokers Responses to Television Advertisements about the Serious Harms of Tobacco Use: Pre-testing Results From 10 Low- to Middle-Income Countries’ Tob Control. 22(1):24-31 https://www.jstor.org/stable/43289293

- El-Sayed, A.M., Palma, A., Freedman, L.P. and Kruk, M.E (2015) ‘Does Health Insurance Mitigate Inequities in Non-Communicable Disease Treatment? Evidence from 48 Low- and Middle-Income countries. Health Policy 2015: 119: 1164– 1175.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168851015001840

- Shroff, Z.C., Thatte, N., Malarcher, S., Maggwa, B., Lamba, G., Babar, Z.U. and Ghaffar, A. (2021) ‘Strengthening Health Systems: The Role of Drug Shops’. J Pharm Policy Pract. 14(Suppl 1):86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-021-00373-0

Grants and Business Development Specialist

We are seeking a highly motivated and experienced Grants and Business Development Specialist to join our organization. The successful candidate will be responsible for identifying funding opportunities, developing grant proposals, and fostering partnerships with potential donors and stakeholders (regional and global). This role plays a vital part in securing funds and resources to support our organization’s mission and projects.

Apply NowPublic Health Consultant, Guinea

The consultant (working with the Accelerator team) will collect results from the tool, organize a meeting with stakeholders to discuss results from the tool, and produce a report on key findings and recommendations from the tool to be shared publicly.

Apply NowPublic Health Associate, Senegal

We are currently in search of an experienced Public Health professional in Senegal to work on the anticipated Nutrition Capacity Development and Financing Platform and provide technical assistance to elevate nutrition financing and strengthen local capacity to support these efforts. The Associate must be bilingual (English and French).

Apply Now